Meditating in the Field—Singapore

He shall

cover you with His feathers,

And under His wings you shall take refuge;

His truth shall be your shield and buckler.

You shall not be afraid of the terror by night,

Nor of the arrow that flies by day,

Nor of the pestilence that walks in darkness,

Nor of the destruction that lays waste at noonday.

A thousand may fall at your side,

And ten thousand at your right hand;

But it shall not come near you. (Ps 91:4–7)

As I reflected on these verses, I was into

my fourth day of self-isolation. That day, I also became part of national

statistics of confirmed COVID-19 cases. Sore throat, fatigue, headache, and

body ache. “Get some food at the supermarket and go home to rest. Drink more

water ah, ah-girl,” the doctor instructed. In my drowsiness, I nodded

obediently, saluted him, and wondered how the old man before me could withstand

the virulence of COVID-19 when seeing so many patients in a day. At home,

drifting in and out of consciousness between bouts of coughing and throat

pain-induced silence, I endured on. In the liminal space between life and

death, my mind began to wander. Has God’s arm been shortened? Have I become

one of the thousands and ten thousands that fell beside me? In theory, we

should not fear, but in practice, we all do. Can the discrepancy between the

Scripture and the number that reflects the reality of sickness and death be

reconciled? Especially when the number also includes many who have been

faithful to the Lord.

My fragmented thoughts were intermittently interrupted

by the screaming of ambulance sirens in the distance.

Since the pandemic outbreak at the end of

2019, the world has danced with the virus as it moves and mutates. People,

capitals, and commodities that once circulated en

mass around the globe came to a standstill. In April 2020, the densely

populated city-state of Singapore implemented its first circuit-breaker (or

lockdown) in an effort to curb the viral infection. Changi Airport, which once

thronged with travelers, became eerily empty. Responding to the choreography of

the virus, people put on masks, rubbed hands with sanitizers, washed hands,

maintained safe distancing, and scanned their phones upon entering public spaces.

Passersby walked briskly through the Central Business District along Orchard

Road, gazing downward with anxiety perched on their brows. As the choreography

of the virus evolved, people configured and reconfigured their gatherings of

duets, trios, fives, eights, and finally, tens. At work and school, people

coordinated in shifts of staggered arrangement.

COVID-19 is more than a pandemic of viral

infection. It leads to other forms of physical, mental, sociocultural, and

financial pandemics. From Delta to Omicron and its subvariants, I seek to

reflect on God’s will through viral choreography. By allowing His people to

dance with the virus, I ask, what does God want me to become? In what ways has

God challenged my ingrained assumptions about Him and my relationship with Him?

How has my understanding of Him evolved as a result?

UNDERSTANDING SUFFERING BEYOND THE DUALISM OF GOOD AND EVIL

Job emerges as one of the most studied

biblical characters since the pandemic erupted.

Our

understanding of him, a human being made to undergo profound suffering, grows

in complexity and nuance with increasing prevalence of Covid infection and

reinfection. In the eyes of his friends, Job’s suffering is commensurate with

his wrongdoing. Their reasoning is straightforward. Good deeds yield good; evil

deeds yield evil. This principle has been taught to generations through the

Mosaic Law, reinforced in King Solomon’s wisdom books, and reiterated in the

prophets’ warning messages throughout the Old Testament. Even Jesus’ disciples

reason in the same way. When meeting a man born blind, they ask Jesus if it is

because of his sin or the sins of his parents (Jn 9:3). Judging by Job’s

immense suffering, his friends conclude with certainty he must have erred in

the eyes of God while still insisting himself to be righteous (Job 31).

Pre-pandemic, it was easy to fall into the

thinking mode of Job’s friends. At the onset of the pandemic, stigmatization

often followed those infected. We wondered to ourselves that perhaps their

suffering was divine punishment for something they had done. However, as the

virus continues to mutate, we take turns walking in the shoes of Job and his

friends. In Singapore, at the time of writing, at least sixty percent of the

population has been infected. People take turns to play the roles of the sick

and the caregiver, the weak and the strong, the consoler and the consoled.

Through this constant role-switching process, we gradually see Job with greater

empathy. The figure of Job is no longer the distant Other. We are concurrently

Job and his friends. We begin to understand that many reasons contribute to

human suffering. The cause of suffering is far more complex than the simplistic

dualism of good-yields-good versus evil-yields-evil formula. Suffering could result

from multiple factors and agents from the material and spiritual worlds coming

into interaction. Only God sees the entire picture and into the future.

SUFFERING IS EXTRA-ORDINARY

Suffering is an extra-ordinary experience.

Though suffering is not uncommon, it is immensely significant to the sufferer.

It disrupts the ordinariness of everyday life by throwing us off our usual

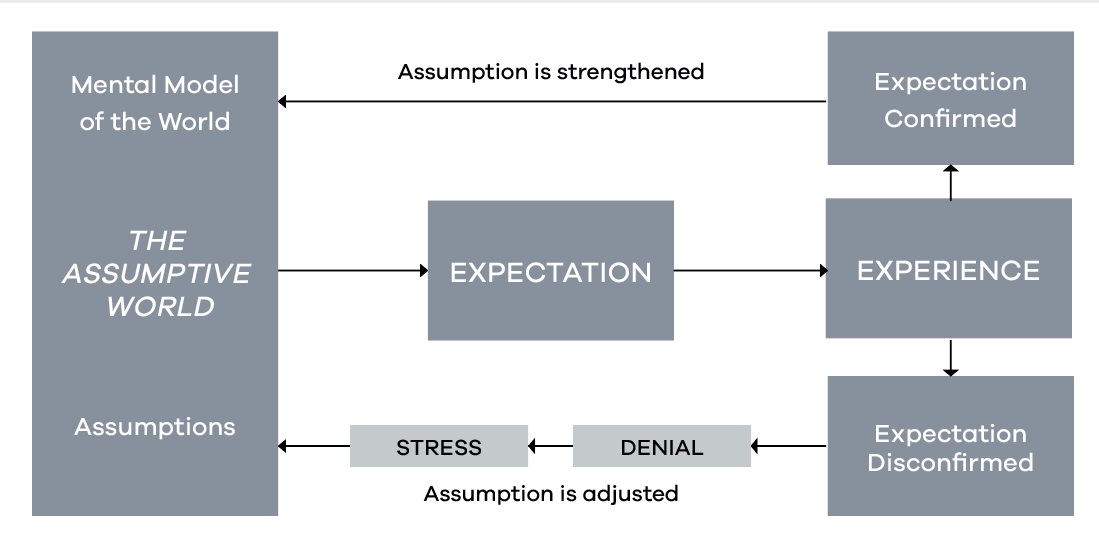

rhythms and routines. Suffering disappoints, saddens, and deprives us. In life,

we have expectations. For instance, we may envision the kind of school we want

to study at, the kind of career path we want to take, the kind of family we

want to build, and the kind of retirement we eventually want to enjoy. We may

also expect to stay healthy and that our children will exceed our own accomplishments.

When we go through an experience in life that confirms our expectations, it, in

turn, reinforces the worldview that we hold. Yet when we undergo an experience

that disconfirms our expectations, we go through stressful phases of denial and

adjustment in which we alter our expectations and worldview. This psychological

transition could last for years, decades, or even a lifetime and is well

documented and studied in trauma research.

Remember Job’s torrent of complaints? Yes,

he is thinking aloud to figure out what went wrong. He is also readjusting his

expectations in life and his relationship with God. In short, Job’s ordinary

life is disrupted when suddenly deprived of wealth, family, and health. He is

grappling with an extra-ordinary experience so much greater than him that he

cannot comprehend, explain, or completely accept. It is difficult, if not

impossible, to remain silent when much pain, bitterness, and disillusionment

are pent up inside.

REMAINING SILENT AND PRAYERFUL IN SUFFERING

Yet silence is golden when in suffering.

When eventually confronted by God, Job replies:

“Behold, I am vile;

What shall I answer You?

I lay my hand over my mouth.

Once I have spoken, but I will not answer;

Yes, twice, but I will proceed no further.” (Job 40:4–5)

Similarly, in Jeremiah’s lamentation over

Israel’s plight, he concludes:

“It is good that one should hope and

wait quietly

For the salvation of the LORD. …

Let him sit alone and keep silent,

Because God has laid it on him.” (Lam 3:26, 28)

When Paul suffers criticism from the

church, he responds:

But with

me it is a very small thing that I should be judged by you or by a human court.

In fact, I do not even judge myself. ...Therefore judge nothing before the

time, until the Lord comes, who will both bring to light the hidden things of

darkness and reveal the counsels of the hearts. (1 Cor 4:3, 5a)

As human beings, we like the reassurance of

clear and quick answers. They settle us with a sense of security. They

guarantee that no further intellectual hard work or soul-searching is required

on our part. In contrast, silence denotes indeterminacy and inconclusiveness.

There is a lack of closure. Yet remaining silent is a powerful assertion of

God’s absolute sovereignty. It is also the sufferer’s resolution to honor that

sovereignty.

What does God want us to do when in

silence? In the depth of a pit, Jeremiah calls on the name of the Lord (Lam

3:55). He knows God does not willingly bring affliction or grief to the

children of men (Lam 3:33). When Jonah is trapped in the belly of a giant fish,

he prays:

Yet You

have brought up my life from the pit. …

When my soul fainted within me,

I remembered the LORD;

And my prayer went up to You,

Into Your holy temple. (Jon 2:6b–7)

After communing with God, Jonah returns to

his mission. Similarly, Job’s conversation with God is a series of prayers that

allows him to process his suffering. In the end, Job recalibrates his

understanding of God and his own positioning. He professes, “I have heard of

You by the hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees You” (Job 42:5). Through

trauma, denial, and finally re-comprehending his relationship with God, Job is

released from his suffering.

WE ARE JOB AND HIS FRIENDS

If remaining silent and prayerful is God’s

will for those in suffering, what then is God’s desire for those who keep their

company? Job’s three friends are certainly on the right track at the start.

They come together by agreement and visit Job with the intention of comforting

him. In deep grief, they sit with him seven days and nights. No one says a word

upon witnessing Job’s immense suffering. However, after hearing Job’s

complaints, Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar become judgmental. They take turns to

expound on God’s justice. Their knowledge of God is unimpeachable. But none of

them can identify the cause of Job’s suffering. Elihu, a young man who waits

for his turn to speak, eventually becomes frustrated by all three of them

because they condemn Job before they can even convince him (Job 32:3).

Through the viral choreography of COVID-19,

God has shown us we can be Job or his friends at any point in time. With the

help of historical hindsight recorded in the Bible and through the study of

psychology, we could argue that Job is going through a transition process after

a major trauma. If it is God’s will for an individual to go through a period of

readjustment, those surrounding him or her are in no place to come to their own

conclusions. At this juncture, Job needs his friends’ presence, prayers, food

supplies, and access to daily necessities. Their company and prayers are to

spiritually uplift Job in overcoming the extra-ordinary experience he is going

through. The friends provide food and daily necessities to maintain the

ordinary routine of Job’s everyday life, which would make him feel grounded. If

we refer to Brennan’s socio-cognitive model of transition in Appendix 1, where

would you place yourself in the diagram as a friend? If you were Job, where

would you like to place your friend? Take out a pen and draw yourself into the

diagram.

By dancing with the virus for the last

three years, we come to understand that we can be Job or his friends at any

given point in time. When we are Job, remaining silent and prayerful is golden

in times of trials and tribulations. When we are his friends, God requires us

to bring comfort—through our presence, prayers, non-judgment, and provision of

food and daily supplies.

Appendix 1:

Figure 1: Adapted from Social-Cognitive

Transition Model of Adjustment (Brennan 2001)